[I am an employee of Celgene. All opinions expressed here are my own.]

A meeting was recently convened to discuss a roadmap for understanding the genetics of common diseases (search Twitter for #cdcoxf18). I presented my vision of a genetics dose-response portal (slides here; link to related 2018 ASHG talk here). The organizers (@RachelGLiao, @markmccarthyoxf, @ceclindgren, Rory Collins [Oxford], Judy Cho [New York], @NancyGenetics, @dalygene, @eric_lander) asked participants to share their vision. I thought I would blog about my mine.

You’ll notice my vision is ambitious. Nonetheless, I believe these objectives are feasible to accomplish within a 3-year (Phase 1) and 7-year (Phase 2) time frame. Phase 1 would start immediately and would guide projects for Phase 2. In reality, many aspects of Phase 1 are already underway today (e.g., GWAS catalogue at EBI; Global Alliance for Genomics and Health [GA4GH] data sharing methods). Phase 2 consists of two parts: federation of global biobanks and experimental validation of variants, genes and pathways. Some components of Phase 2 could start today (e.g., exome sequencing in >100,000 cases selected from existing case-control cohorts and biobanks; human knockout project). As with Phase 1, many components of Phase 2 are already underway (federation of existing biobanks [e.g.,…

Read full article...

[I am an employee of Celgene. All views expressed here are my own.]

What is the clinical significance of residing within the tail of a distribution for disease risk? A new study published in Nature Genetics uses a composite polygenic score to measure extremes of genetic risk(see original article here). The authors make the bold statement: “it is time to contemplate the inclusion of polygenic risk prediction in clinical care”. In this plengegen.com blog, I briefly review the paper, frame the impact of the study in terms of “long tails”, and propose how genetic tails may be used as part of a healthcare system reimagined.

The premise of the paper is that a genome-wide polygenic score (GPS) – a composite genetic test that includes thousands and sometimes millions of genetic variants – can identify a small number of individuals from the general population that have an elevated risk. The study applies polygenic risk scores to five common diseases but spends most attention to coronary artery disease (CAD). For each disease, the increase in risk is approximately 3- to 5-fold higher among individuals at the extreme of the polygenic tail compared to those in the general population – see Figure 2a (and below) for CAD, where ~8% of the general population is at a 3-fold increase in risk based on a polygenic risk score.…

Read full article...

I have many fears, both professional and personal. When I decided to leave academics for a job in industry in 2013, my biggest fear about making the transition was scientific. In my mind, I had a model of how human genetics might transform drug discovery and development. There were anecdotes (e.g., PCSK9 inhibitors) and a few systematic studies in specific diseases (e.g., genetics of rheumatoid arthritis), but there were many holes to the model. Over the last couple of years, additional anecdotes and systematic analyses have emerged (e.g., Matt Nelson, et al. Nature Genetics), which helps to soothe my fears…but I still have concerns.

[Disclaimer: I am a Merck/MSD employee. The opinions I am expressing are my own and do not necessarily represent the position of my employer.]

As I have blogged about previously, I see two primary routes to go from human genetics to new drug discovery programs (see here, here). The first requires that there are genes with a series of disease-associated alleles with a range of biological effects, ideally from gain- to loss-of-function (allelic series model). The second requires disease-associated genes to aggregate within specific biological pathways, which can then be turned into assays for disease-relevant pathway-based screens such as phenotypic screens.…

Read full article...

I attended the Mendelian randomization meeting in Bristol, UK this past week (link to the program’s oral abstracts here). The meeting was timed with the release of a number of articles in the International Journal of Epidemiology (current issue here, Volume 44, No. 2 April 2015 TOC here). This blog is a brief synopsis of the meeting – with a focus on human genetics and drug discovery. The blog includes links to several slide decks, as well as references to several published reviews and studies.

[Disclaimer: I am a Merck/MSD employee. The opinions I am expressing are my own and do not necessarily represent the position of my employer.]

Several speakers, including Lon Cardon from GSK, gave overview talks on how Mendelian randomization can be applied to pharmaceutical development. In my overview, I described important guiding principles for successful drug discovery (link to my slides here), and how Mendelian randomization (MR) is applied within this framework. In particular, I emphasized the role of establishing causality in the human system: MR is a powerful tool to pick targets by estimating safety and efficacy (i.e., genotype-phenotype dose-response curves) at the time of target identification and validation; MR is effective at picking biomarkers for target modulation; and MR provides quantitative modeling of clinical proof-of-concept (POC) studies.…

Read full article...

In this post I will build on previous blogs (here, here, here) about genetics for target ID and validation (TIDVAL). Here, I argue that new targets with unambiguous promotable advantage will emerge from studies that focus on genetic pathways rather than single genes.

This is not meant to contradict my previous post about the importance of genetic studies of single genes to identify new targets. However, there are important assumptions about the single gene “allelic series” approach that remain unknown, which ultimately may limit its application. In particular, how many genes exist in the human genome have a series of disease-associated alleles? There are enough examples today to keep biopharma busy. Moreover, I am quite confident that with deep sequencing in extremely large sample sizes (>100,000 patients) such genes will be discovered (see PNAS article by Eric Lander here). Given the explosion of efforts such as Genomics England, Sequencing Initiative Suomi (SISu) in Finland, Geisinger Health Systems, and Accelerating Medicines Partnership, I am sure that more detailed genotype-phenotype maps will be generated in the near future.

[Note: Sisu is a Finnish word meaning determination, bravery, and resilience; it is about taking action against the odds and displaying courage and resoluteness in the face of adversity. …

Read full article...

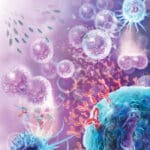

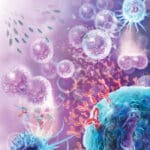

This blog post pertains to the Systems Immunology graduate course at Harvard Medical School (Immunology 306qc; see here), which is led by Drs. Christophe Benoist, Nick Haining and Nir Hacohen. My lecture is on the role of human genetics as a tool for understanding the human immune system in health and disease. What follows is an informal description of my lecture. The slide deck for the lecture can be downloaded here. Throughout, I have added key references, with links to the manuscripts and other web-based resources embedded within the blog (and also listed at the end). I highlight five key manuscripts (#1, #2, #3, #4, and #5), which should be reviewed prior to the lecture; the other references, while interesting, are optional.

Overview

It is increasingly clear that humans serve as the best model organism for understanding human health and disease. One reason for this paradigm shift is the lack of fidelity of most animal models to human disease. For systems immunology, the mouse is a powerful model organism to understand fundamental mechanisms of the immune system. However, studies in humans are required to understand how these mechanisms can be translated into new biomarkers and drugs.…

Read full article...

The value of genetics to clinical prediction depends upon the underlying genetic architecture of complex traits (including disease risk and drug efficacy/toxicity). It is increasingly clear that common variants contribute to common phenotypes, but that extremely large sample sizes are required to tease apart true signal from the noise at a stringent level of statistical significance. Occasionally, common variants have a large effect on common phenotypes (e.g., MHC alleles and risk of autoimmunity; VKORC1 and warfarin metabolism), but this seems to be the exception rather than the rule.

A recent paper published in Nature Genetics explores this concept in more detail (download PDF here). As stated in the manuscript by Chatterjee and colleagues: “The gap between estimates of heritability based on known loci and those estimated owing to the comprehensive set of common susceptibility variants raises the possibility of substantially improving prediction performance of risk models by using a polygenic approach, one that includes many SNPs that do not reach the stringent threshold for genome-wide significance.” They measure the ability of models based on current as well as future GWAS to improve the prediction of individual traits.

The results, which are intriguing, depend not only on the underlying genetic architecture (which is often unknown, especially for PGx traits), but also disease prevalence and familial aggregation: “We observed that for less common, highly familial conditions, such as T1D and Crohn’s disease, risk models that include family history and optimal polygenic scores based on current GWAS can identify a large majority of cases by targeting a small group of high-risk individuals (for example, subjects who fall in the highest quintile of risk).…

Read full article...