Early in my career, I was often asked, “Do you want to work in academia or industry?” The emphasis was always on “or,” a clear line drawn between the supposed ivory tower of academia and the commercially driven environment of industry. The way the question was framed made it clear: there were discrete tracks of scientific pursuit, and at some point, scientists needed to choose one track or another.

Moreover, the connection between these tracks was always portrayed as being very linear. Foundational research happened in academia. Smaller companies would advance those findings in drug discovery and development programs. Ultimately, large pharmaceutical companies would usher new treatments through FDA approval and commercialization. It was like a 400-meter relay, where each player ran a segment of the race and then handed off the baton to the next in line.

That model worked for a time, but science has outgrown the simplicity of a relay race. Today, the reality looks very different. The life sciences field is now highly interconnected, collaborative, and far more complex. It’s less like a relay and more like a forest – vibrant, diverse and interdependent.

Given this evolution, rather than “or,” I believe we should be talking about “and” – academia and industry (link here), biotech and Big Pharma, venture capital and public funding…and, And, AND!

In this blog, I want to talk about “and” science – or what I refer to as “blended innovation.” Today the life sciences industry is far more integrated and interdigitated than ever before, with collaboration occurring across all stages of scientific research. We have created a true ecosystem, where groups work together to advance science on behalf of patients. I believe the future of drug discovery and development hinges on our ability to nurture that ecosystem, so that it flourishes and continues to propagate new ideas that will ultimately benefit patients.

Cultivating a life sciences ecosystem

To understand how we got here, let’s look back – with the help of the forest metaphor I described above.

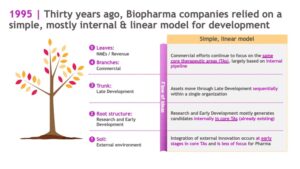

Thirty years ago, the biopharma industry was like a row of saplings: young and growing vigorously, but with a relatively simple structure. During this stage of tree life, a sapling is internally focused; the biggest priorities are root system development, rapid growth, and survival.

In the same way, biopharma companies in the 1990s relied on a simple, mostly internal and linear model for development. External innovation was primarily sourced at early stages of research in core therapeutic areas. Research and Early Development programs mostly generated drug candidates internally, and assets progressed through Late Development sequentially within a single organization.

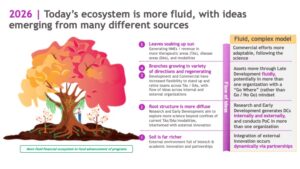

Jump to 2025, and the industry has evolved into a mature forest, with rich soil, interconnected root systems and diverse tree species.

More than just a collection of trees, forests are complex systems involving symbiosis and cooperation. Trees in mature forests aren’t competing for resources; they are forming cooperative networks and sharing resources amongst each other to ensure the continued growth and development of the forest as a whole.

Much like a real forest, the life sciences ecosystem of today is highly interconnected and interdependent, rooted in rich science. We are no longer living in an era where a medicine follows a straight, internal path from discovery through development and commercialization. Today you might find that a potential medicine takes a winding path from academia to biotech (maybe more than one…) to pharma, with inputs from different stakeholders in the ecosystem, who nurture the medicine until it reaches its fullest potential.

Today, there is innovation happening across the ecosystem – from academic institutions to biotechs and pharma – providing opportunities for fruitful partnerships. There are also funding mechanisms in place to facilitate the movement of ideas from academia into small companies, and large companies are more willing to do deals. The expertise gap between small and large companies has also closed, with deep benches of talented scientists at both small startups and large pharmaceutical companies.

In short: we now have better science, more ample funding, and a larger talent pool, which creates an environment that can deliver better medicines for patients.

Importantly, in this environment, there isn’t a single path from an idea to an approved medicine. The richness and complexity of our life sciences ecosystem means that the trajectory of each medicine is unique and different. That’s a good thing! The more we can leverage unique blended models to take therapies from the bench to the bedside as efficiently as possible, the more we will be able to help patients who are waiting for new and better treatments.

Blended innovation in action: The journey of a medicine

This interconnectedness isn’t just theoretical – it’s shaping real medicines today. To bring this blog down from the treetops (pun intended), let’s look at an example that shows how blended innovation works in practice.

Journey #1: anti-PD1 therapy in oncology

Consider the journey of BMS’ anti-PD-1 cancer immunotherapy, a therapy now widely used to treat advanced cancers. Its origins trace back to early academic research, with Dr. Tasuku Honjo at Kyoto University discovering the PD-1 receptor, a key immune checkpoint that can suppress the body’s ability to attack tumor cells. Seeing the promise in targeting PD-1, scientists at Medarex, a biotech company specializing in monoclonal antibodies, began engineering antibodies to block this pathway in close collaboration with Honjo’s team.

Medarex’s work produced an antibody capable of inhibiting PD-1, laying the foundation for anti-PD-1 therapies. In 2009, BMS acquired Medarex, bringing additional expertise and resources to accelerate clinical research and development. This partnership helped advance BMS’ anti-PD-1 therapy through trials for various cancer types. In 2014, the therapy received its first regulatory approval, marking the beginning of its global availability.

The development of BMS’ anti-PD-1 therapy is a clear example of blended innovation at work: foundational academic research sparked biotech advances, which were then propelled forward by large-scale pharma expertise, regulatory navigation, and global commercialization. Rather than a straight line, this journey was shaped by scientific breakthroughs, strategic partnerships, and continuous collaboration across the entire ecosystem.

Journey #2: myosin modulators in cardiomyopathies

Another fascinating journey is that of myosin inhibitors and activators for the treatment of cardiomyopathies. Genetic evidence for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) originated in 1990, with the discovery a myosin mutation in a gene that is part of the sarcomere complex, the MYH7 mutation R403Q. Since that time, >100 variants have been described in MYH7. It took another decade of academic research to understand the mechanistic implications of these and other sarcomere mutations. More detail, together with references, can be found in this slide deck.

Based on these insights, Third Rock Ventures incubated a new company, MyoKardia, which launched in 2012 (link here). MyoKardia was built on the academic work of Stanford’s James Spudich, Harvard’s Christine (Kricket) and Jonathan Seidman, and University of Colorado’s Leslie Leinwand. In 2014, MyoKardia partnered with a large biopharma (Sanofi) to advance their lead asset, mavacamten (link here). After four years (2019), the terms of the partnership expired, and both parties elected not to renew the relationship (here). Consequently, MyoKardia advanced mavacamten successfully through Phase 3 clinical development. BMS acquired MyoKardia after the completion of the pivotal Phase 3 clinical trial for mavacamten, EXPLORER-HCM (here). BMS subsequently navigated mavacemten through regulatory approval and commercial launch.

There is one more twist to the blended journey that has yet to unfold: BMS out-licensed one of the investigational medicine’s acquired through MyoKardia to a new company, Kardigan (here). Many of the founders of Kardigan were also founders and executives at MyoKardia. The investigational medicine, danicamtiv, is in Phase 2b development for dilated cardiomyopathy.

Journey #3: BMS-Bain Immunology NewCo

On final example of blended innovation is a recent spinout of immunology assets from BMS to a NewCo funded by Bain Capital Life Sciences (links here, here). The new entity began operations with five in‑licensed assets from BMS across a range of autoimmune indications—three clinical‑stage programs and two Phase 1 candidates. The most advanced among these are afimetoran, an oral TLR7/8 inhibitor in Phase 2 trials for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and BMS‑986322, an oral TYK2 inhibitor with positive Phase 2 data in plaque psoriasis. Both programs have strong genetic evidence supporting the therapeutic hypothesis, most of which emerged from academic research over several decades (see links here, here, here, here).

By sharing knowledge, resources, and expertise at every stage, diverse contributors helped move an initial idea from early discovery to broad clinical use, demonstrating the true strength of our interconnected life sciences “forest.” If you would like to read more examples of blended innovation, I encourage you to read Dr. William Pao’s book, Breakthrough: The Quest for Life-Changing Medicines (reviewed here).

Continuing to evolve the blended model

These stories illustrate the power of collaboration but also raise important questions about what’s next. How do we continue to evolve this blended model to unlock even greater potential?

No matter how healthy and diverse our ecosystem might be, there are some foundational truths when it comes to scientific innovation.

First, fundamental innovation takes time. To whatever extent AI and ML are enabling scientists to accelerate scientific discovery, the reality is that breakthroughs don’t happen overnight. They happen over time – often decades. Thus, academia is well-suited to this type of fundamental science because there are fewer constraints and less emphasis on a defined endpoint. A large pharmaceutical company might not be the one to invent CRISPR – even if they ultimately might find the best way to turn it into a treatment.

Second, drug development is rarely linear. Given the breadth and depth of our life sciences ecosystem, by the time a drug reaches a patient, many stakeholders’ hands have touched that medicine. From an industry perspective, then, it’s less interesting to think about whether a product was an internal or external drug candidate. A far more interesting question is: what was this molecule’s journey? And how can that journey inform future collaborations? Once we start appreciating the power of blended innovation, we can start to think of ways we can leverage that model to challenge the status quo.

And, to be clear, we should challenge the status quo. The blended model within our ecosystem is working well – but could it be working better? Could we evolve this blended model to expand our reach even further and access new biology, modalities, assets and capabilities? It’s a fair question and one I think we need to ask as an industry.

Indeed, given the foundational truths above, it makes sense that drug discovery funding generally flows from the NIH and foundations (academia) to venture capital (small biotechs) to public investors (large pharma). Is there a different model that might work just as well – or better? Perhaps higher education could be involved throughout. Or maybe there are creative collaboration models with organizations or companies in China that could accelerate discovery. AI has already helped scientists accelerate aspects of drug discovery and development; are there ways we could leverage this technology to enhance our blended model?

The answers to these questions will be crucial in determining how tall our “trees” can grow – and how resilient our ecosystem can become. The future of drug discovery depends on our willingness to challenge old models, embrace new partnerships, and cultivate an ecosystem where ideas can take root and thrive. If we succeed, the ultimate beneficiaries will be the patients who rely on us to turn scientific possibility into life-changing reality.

[ A pdf link to this blog post can be found here. ]